The voice of a photographer of war and, sometimes, of peace / La voce di un fotografo di guerra e, a volte, di pace

by/di Simona Maria Frigerio (Translation into Italian at the bottom of the page)

While Italian troups are leaving Afghanistan, it can be of some interest to read the interview to a reporter who has spent 40 years of his life as a war reporter – most of the time embedded with the US Army, even in Iraq and Afganistan.

I’ve never met Sebastian Rich but when I saw one of his photos of a smiling child in a war zone, I thought that something beautiful – or merely human – does still survive even in the worst situations. I asked him this interview and didn’t think he would bother to reply. Instead, he did it and without clichés. Here is the story of a photographer of war: his thoughts and fears, hopes and beliefs. It’s very interesting to listen to him telling us those stories he usually captures on his cameras because, strangely enough, his voice is as powerful as his photos.

You describe yourself as a photographer of war and occasionally of peace. But, at the moment, you are portraying smiling children. Why?

Sebastian Rich: «Why! Why! Because I need the world to smile back at me, I have photographed so much utter devastating shit that I need to know that there is happiness somewhere, anywhere in the world. The irony is that all the smiles that I have captured have been in war zones or areas of severe conflict. Somehow, these children in the most awful circumstances have always managed to smile at my lens. But because the world wants to see sensationalism in the form of brutality these wonderful smiles are on the whole ignored by picture editors. I think it’s about time I became part of the solution and not remain part of the problem».

Your portraits are both colour and black & white. How do you decide?

S. R.: «I have two cameras around my neck, both digital – but one is switched to black and white. It’s a subconscious thing. I just instinctively know how the image unfolding in front of me should be represented in colour or black and white. But I do have to admit that I find colour for heavy duty reportage most distracting. Somehow, blood is far more powerful in black and white. One’s imagination takes over and fills in the colour spectrum to much better effect than have you soaked in colour».

You work with the Malala Yousafzai Foundation (whose founder is Nobel Peace Prize 2014). After so many years of war, what is the situation of women in Pakistan and Afghanistan?

S. R.: «The situation for the women of Afghanistan and Pakistan is exactly the same as it was a millennia ago. Women are chattel to the men of these countries. Their status in the family circle is one just above the cow and the bicycle. An object of abuse and sexual slavery, however we – the West – might want to help and relieve the suffering of woman kind in Afghanistan and Pakistan, nothing changes. Until we rid the world of religious fanaticism and arrogant male ego nothing will change, nothing».

You have taken pictures of soldiers who have PSTD syndrome. Most people don’t know what it is. Is there anyone who helps them or are they left by themselves?

S. R.: «I have it; my friends, soldiers and photographers alike have it. Certainly the British and US military are very good with their counseling nowadays! But for the likes of me and my freelance friends, we live everyday with our nightmare, some of us have coping mechanisms, some do not and fall to a darker place that I know all too well».

In Iraq you were an embedded reporter. Is it possible to remain objective in such a situation?

S. R.: «Absolutely not, there is no such thing as objectivity! We all have an agenda of some kind, however subconscious. We like to think we are objective but we are not. Especially in the embedded process! I was with the US Marines all through the ground war in Iraq. Young Marines saved my life on many, many occasions. When it came their turn to die or be wounded in front of my camera I was bound by the confines of comradeship and loyalty. How could I photograph these broken young bodies knowing all about their parents, girlfriends and their private lives? Maybe if the embedded is a short week event then, yes, it might be easier. But nowadays I think too much and whenever I see an injustice I will do my best to tell that story so that the perpetrators are held responsible».

In Vietnam people call the war, the American war, but the public opinion in the Western world call it the Vietnam war. How do people in Afghanistan and Iraq see military operations in their countries? And, on the other hand, have American soldiers any doubts about war?

S. R.: «The Afghans on the whole see all outside military operations in their country as an abomination to their society. But the alternative of living under strict Taliban Sharia law is also to the average people of Afghanistan another terrible evil! We – the West – see the war in Afghanistan as freedom for the Afghan people. I am so sad thinking about the sacrifices of soldiers of all nations and civilians on both sides, who have been slaughtered in great numbers. But now I think it is time for Afghanistan to look to its own fate and place in the world».

In Italy there was a young journalist and peace activist, called Vittorio Arrigoni, killed in Gaza, who believed that “another world is possible”. What do you think?

S. R.: «I would so very much like to have the optimism of dear Vittorio about our little terrified and sad planet! I have become a terrible cynic in my years of photographing the worst that man has to offer and I have come to the conclusion that we will never change our warlike nature! It’s too late even if by some miracle we could all settle our differences with calm meaningful words of wisdom, it’s too late: we have destroyed our planet environmentally for us to have any future. I am so sorry for my dark thoughts but for me this is the truth».

Changing subject, in the last few years you have been photographing dancers. But also in your war shots we can find some kind of beauty and sensibility. For Nouvelle Vague it isn’t possible to depict something horrible as a war through beautiful images. What do you think?

S. R.: «For over forty years I have been photographing the very worst that mankind has had to offer my lens. But here, there is the paradox – on many occasions, an image I capture of someone in his or her most quintessential moment of loss or terror, in some disgusting war, has been remarked on as ‘beautiful’. This well-meaning and flattering remark about my photography rests very uneasy with me. I get it – and at the same time I don’t! In my youth as an arrogant young photographer I thought that the people that I was photographing were there for no reason other than to further my career! So then, to have the compliment of: “It’s beautiful” was most rewarding. As the years moved on – in some respects I grew up. Not all, but some. It took a catastrophe to knock the stupidity and arrogance from my young bones. A catastrophe that killed two soldiers and sent hot screaming metal through my stomach. I became the victim – the photographed, the exploited and the frightened. Now I spend time, maybe too much time with my subjects, as one client was to remark just recently. I listen to their stories in great detail, as sometimes I am the only one who will listen, or remotely care. At some point I will take their photograph, I will hardly notice that I have done so, nor will they. Maybe it’s a technique, but it’s a subconscious one. Why does poverty, war, famine throw up such sharp, hard beauty? I have no idea, as photography is so utterly subjective. As a war photographer, I have witnessed unspeakable acts of violence. I had to photograph something beautiful, something/anything to save my soul. There comes a time in the life of some in my profession that we cry out for beauty and a gentleness that is missing in our lives. I have reached that stage».

1st published on Artalks.net, October 31, 2014 – Newly translated into Italian, Friday, June 18, 2021

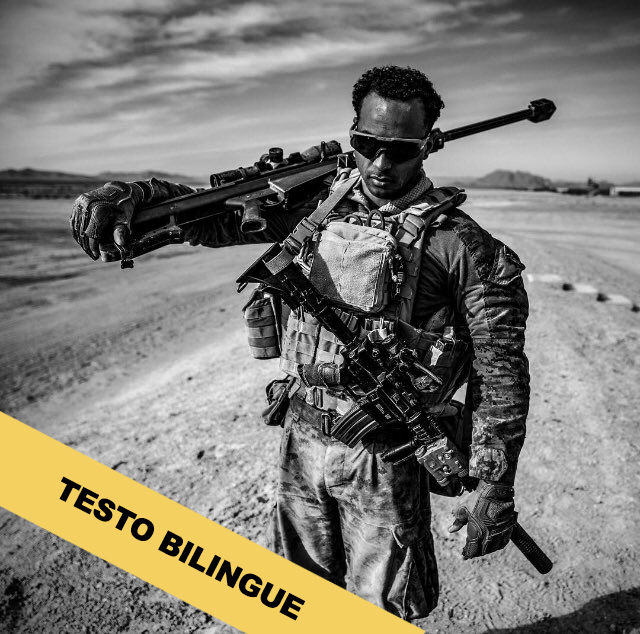

On the cover: Afghanistan, 2019. Photo by Sebastian Rich. Courtesy Sebastian Rich (all rights reserved).

Testo italiano

Traduzione di Simona Maria Frigerio

Mentre le truppe italiane stanno lasciando l’Afghanistan, può essere interessante leggere l’intervista a un fotografo che ha trascorso quarant’anni della propria vita a fare il reporter, per la maggior parte del tempo al seguito dell’esercito statunitense – ivi compresi Iraq e Afganistan.

Non ho mai incontrato Sebastian Rich di persona ma quando ho visto una delle sue foto con un bimbo sorridente in zona di guerra, ho pensato che qualcossa di bello – o sempliceme di umano – sopravvive anche nelle peggiori situazioni. Gli ho chiesto l’intervista non pensando che si sarebbe curato di rispondere; al contrario, lo ha fatto – ed evitando i cliché. Ecco la storia di in fotografo di guerra: pensieri e timori, speranze e convinzioni. È interessante ascoltarlo raccontare storie che, generalmente, cattura con la macchina fotografica perché, abbastanza stranamente, la sua voce è altrettanto potente delle sue foto.

Lei si descrive come un fotografo di guerra e, occasionalmente, di pace. Ma in questo momento ritrae bambini sorridenti. Come mai?

Sebastian Rich: «Perché? Perché! Perché sento il bisogno che il mondo mi sorrida Ho fotografato così tanta merda letteralmente devastante che ho bisogno di sapere che esiste la felicità da qualche parte al mondo. L’ironia è che tutti questi sorrisi che ho catturato sono fioriti in zone di guerra o aree affette da gravi conflitti. In qualche modo, questi bambini, nelle peggiori circostanze, sono riusciti a sorridere al mio obiettivo. Ma siccome il mondo vuole il sensazionalismo in forma di brutalità questi meravigliosi sorrisi sono totalmente ignorati dagli editori. Penso che è tempo che io diventi parte della soluzione e che non rimanga parte del problema».

I suoi ritratti sono sia a colori sia in bianco e nero. Come sceglie?

S. R.: «Ho due macchine fotografiche appese al collo, entrambe digitali – ma una è posizionata sul bianco e nero. La mia, è una decisione inconscia. Capisco istintivamente come l’immagine che mi si presenta di fronte debba essere rappresentata – se a colori o in bianco e nero. Ma mi tocca ammettere che trovo che il colore, nei reportage più forti, distragga. In qualche modo, il sangue è più potente in bianco e nero. L’immaginazione individuale prende il sopravvento e utilizza l’intero spettro per completare la foto con un effetto migliore che se avessi immerso la stessa direttamente nel colore».

Lei lavora per la Malala Yousafzai Foundation (la cui fondatrice ha vinto il Premio Nobel per la Pace nel 2014). Dopo tanti anni di guerra, qual è la situazione delle donne in Pakistan e Afghanistan?

S. R.: «La situazione delle donne in Pakistan and Afghanistan è esattamente la stessa di mille anni fa. Le donne sono un possesso degli uomini in quei Paesi. Il loro status, nell’ambiente familiare, è appena al di sopra della mucca e della bicicletta. Un oggetto da abusare e di schiavitù sessuale. Per quanto noi occidentali si voglia aiutare e alleviare le sofferenze delle donne afghane e pakistane, non cambia niente. Finché non libereremo il mondo del fanatismo religioso e dell’arrogante ego maschile, non cambierà nulla».

Lei ha fotografato soldati affetti da stress post-traumatico. In molti non sanno cosa sia. Vi è chi li aiuta o sono abbandonati a se stessi?

S. R.: «Ce l’ho anch’io; i miei amici, soldati e fotografi, parimenti. Certamente gli eserciti statunitense e britannico, oggi come oggi, hanno una buona assistenza psicologica! Ma quelli come me e i miei amici freelance, convivono ogni giorno con i propri incubi – alcuni hanno sviluppato strategie adattive, altri no e finiscono in un luogo molto più oscuro, che conosco bene».

Lei era un reporter al seguito dell’esercito (embedded) in Iraq. È possibile restare obiettivi in simili situazioni?

S. R.: «Assolutamente no, non esiste una cosa chiamata obiettività! Abbiamo tutti le nostre priorità, per quanto inconscie. Ci piace pensare di essere obiettivi ma non lo siamo. Specialmente se embedded! Ero coi Marine sul terreno di guerra in Iraq. Giovani Marine mi hanno salvato la vita in più occasioni. Quando è arrivato il loro turno di morire o essere feriti di fronte alla mia macchina fotigrafica, mi sono sentito costretto da legami di cameratismo e lealtà. Come avrei potuto fotografare quei giovani corpi martoriati sapendo tutto dei loro genitori, delle loro ragazze e delle loro vite private? Forse, se si è embedded solo per una settimana, può essere più facile. Ma oggigiorno penso troppo e quando vedo un’ingiustizia faccio del mio meglio per raccontarla, così che i colpevoli siano ritenuti responsabili dei fatti commessi».

In Vietnam le persone ricordano la Guerra Americana in Vietnam, ma l’opinione pubblica occidentale definisce lo stesso conflitto Guerra del Vietnam. Cosa pensa la popolazione afghana o iraquena della presenza militare straniera nel prorio Paese? E, dall’altra parte, i soldati statunitensi non hanno dubbi sulla guerra?

S. R.: «Nel complesso gli afghani considerano tutte le operazioni militari straniere nel loro Paese come un abominio. Ma l’alternativa di vivere sotto la Shariʿah imposta dai talebani, per la media della popolazione afghana, è parimenti un male orribile! Noi occidentali vediamo la guerra in Afghanistan come la liberazione degli afghani. Sono così triste al pensiero del sacrificio dei soldati di ogni nazionalità e dei civili su entrambi i lati, massacrati in gran numero. Ma ora penso che sia tempo per gli afghani di considerare il proprio destino e posto nel mondo».

In Italia c’era un giovane giornalista e attivista, chiamato Vittorio Arrigoni, ucciso a Gaza, che credeva che “un altro mondo è possibile”. Cosa ne pensa?

S. R.: «Mi piacerebbe così tanto condividere l’ottimismo del caro Vittorio circa il nostro piccolo, spaventoso e triste pianeta! Sono diventato terribilmente cinico fotografando il peggio che gli esseri umani hanno da offrire e sono giunto alla conclusione che non cambieremo mai la nostra natura bellicosa! Sarebbe troppo tardi perfino se, per un qualche miracolo, potessimo sistemare tutte le nostre divergenze con tranquille, sensate parole di saggezza – è troppo tardi: abbiamo distrutto il nostro pianeta a livello ambientale a tal punto che è impossibile che noi si abbia ancora un futuro. Mi spiace per questi pensieri neri ma, secondo me, questa è la verità».

Cambiando argomento, negli ultimi anni lei ha fotografato danzatori. Ma persino nei suoi scatti di guerra possiamo scorgere qualcosa di bello e sensibile. Per la Nouvelle Vague era impossibile ritrarre un fatto orribile, come la guerra, attraverso immagini esteticamente belle. Cosa ne pensa?

S. R.: «Per oltre quarant’anni ho fotografato il peggio che l’umanità potesse offrire al mio obiettivo. Ma qui sta il paradosso: in molte occasioni, un’immagine che catturo – di qualcuno o qualcosa che sta vivendo la quintessenza del momento peggiore della sua esistenza, di perdita o terrore, in qualche nauseante guerra – è considerata ‘bella’. Questo commento ben intenzionato e lusinghiero circa le mie foto mi mette a disagio. Lo comprendo – e allo stesso tempo non ci riesco! Quando era un giovane e arrogante fotografo pensavo che le persone che ritraevo non erano lì per nessun’altra ragione che favorire la mia carriera! Allora, ricevere il complimento: “Che bella!” era molto gratificante. Col passare degli anni sotto alcuni aspetti sono cresciuto. Non tutti, ma alcuni. Mi ci è voluta una catastrofe per espellere l’arroganza dalle mie giovani ossa. Una catastrofe che uccise due giovani soldati e mi conficcò nello stomaco metallo bollente da urla. Divenni una vittima – il fotografato, sfruttato e terrorizzato. Ora passo del tempo, forse troppo – come un cliente mi ha fatto notare recentemente – coi miei soggetti. Ascolto le loro storie in dettaglio, dato che a volte sono l’unico a volerle ascoltare, o a cui minimamente interessino. A un certo punto scatto la foto, senza quasi accorgermene, come accade ai miei soggetti. Forse è tecnica, ma se lo è, è inconscia. Perché la povertà, la guerra, la carestia vomitano una tale tagliente bellezza? Non lo so, dato che la fotografia è talmente soggettiva… Come fotografo di guerra, sono stato testimone di atti di una violenza indicibile. Sentivo il bisogno di fotografare qualcosa di bello, qualsiasi cosa per salvarmi l’anima! Arriva un tempo nella vita di alcuni, tra quelli che esercitano la mia professione, in cui si sente la necessità di pretendere un po’ di bellezza e gentilezza. Quella che manca nelle nostre vite. Io ho raggiunto quello stadio».

Per un approfondimento sulla situazione afghana:

Pubblicato la prima volta su Artalks.net, il 31 ottobre 2014 – Traduzione inedita in italiano, venerdì, 18 giugno 2021

In copertina: Afghanistan, 2019. Foto di Sebastian Rich, gentilmente fornita dall’Autore (tutti i diritti riservati).